Factors Affecting Asthma

Research has found that both genetic and non-genetic factors affect asthma. A number of factors may cause exacerbations in people who have asthma but there is no recognised cause, either biological or environmental, for asthma itself. Thus, when considering nongenetic factors, it is important to distinguish between the triggers of asthma attacks and the causes of the underlying asthmatic process or trait. Both groups of factors may contribute to the severity and persistence of asthma.

Who is at risk of asthma?

Genetic susceptibility

Asthma often runs in families, and identical twins are more likely to have the same asthma status than are non-identical twins. Researchers have identified a number of genetic variants that influence asthma risk, mainly in children. However, there is still a great gap of ’missing heritability‘ to be discovered, and the interaction between genes and the environment through epigenetic changes is a current focus for research.

Environmental tobacco smoke

Environmental tobacco smoke has been confirmed as a risk factor for asthma, both in childhood and adulthood. Pre-natal exposure to tobacco smoke is also important. This is considered to be a causal relationship, implying that the prevalence (and severity) of asthma would reduce if exposure to tobacco smoke was reduced.

Air pollution

Evidence of an increased risk of asthma due to indoor air pollutants (e.g. cooking on an indoor open fire) or outdoor air pollutants (e.g. suspension particles or sulphur dioxide) is less clear and consistent than for tobacco smoke.

Mould and damp

Dampness is a potentially modifiable risk factor for asthma worldwide, though its association with asthma is stronger in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) than in high income countries (HICs). This risk is independent of allergic sensitisation to house dust mites, which is more common in damp homes.

Animals

In HICs, exposure to furry pets is often less common among asthmatic children and adults, due to avoidance or removal of pets by allergic families. In LMICs, this avoidance is less common and there is evidence that cats in the home during the first year of life are a risk factor for asthma. Several large studies in HICs have shown a lower prevalence of asthma among children living on farms, but this is probably not so in LMICs.

Antibiotics and paracetamol (acetaminophen)

Asthma symptoms are more common among children treated with antibiotics in early childhood. The direction of cause and effect is uncertain because antibiotics may be given for chest illnesses which could be an early manifestation of asthma. Similar considerations of ‘reverse causation’ apply to the association with paracetamol (acetaminophen) exposure in infancy.

Occupational exposures

Occupational asthma may develop after the prolonged inhalation of certain agents, in people with no previous history of chest disease, and can sometimes persist after exposure to the causal agent is removed. High-risk occupations include baking, woodworking, farming, exposure to laboratory animals, and use of certain chemicals, notably paints containing isocyanates.

Diet and obesity

The available evidence suggests that diets widely recommended to prevent cardiovascular diseases and cancer may slightly reduce the risk of asthma. Thus, ‘fast food’ increases risk and fresh fruit and vegetables appear to be protective against asthma. A link has also been established between obesity and increased risk of asthma, both in children and adults.

Breastfeeding

Prolonged exclusive breastfeeding protects against early respiratory viral infections that cause wheezing in infancy. However, protection from asthma at school age seems confined to nonatopic asthma in LMICs.

Common triggers in asthmatics

Asthma attacks are often triggered by upper respiratory tract infections, including common colds. Other factors that may provoke asthma attacks include inhaled allergens (dust mites, animal fur, pollens, moulds, allergens in the workplace), inhaled irritants including air pollutants (cigarette smoke, fumes from cooking, heating or vehicle exhausts, cosmetics, aerosol sprays), medicines (including aspirin), exercise, emotional stress, and certain foods or beverages.

Recent findings

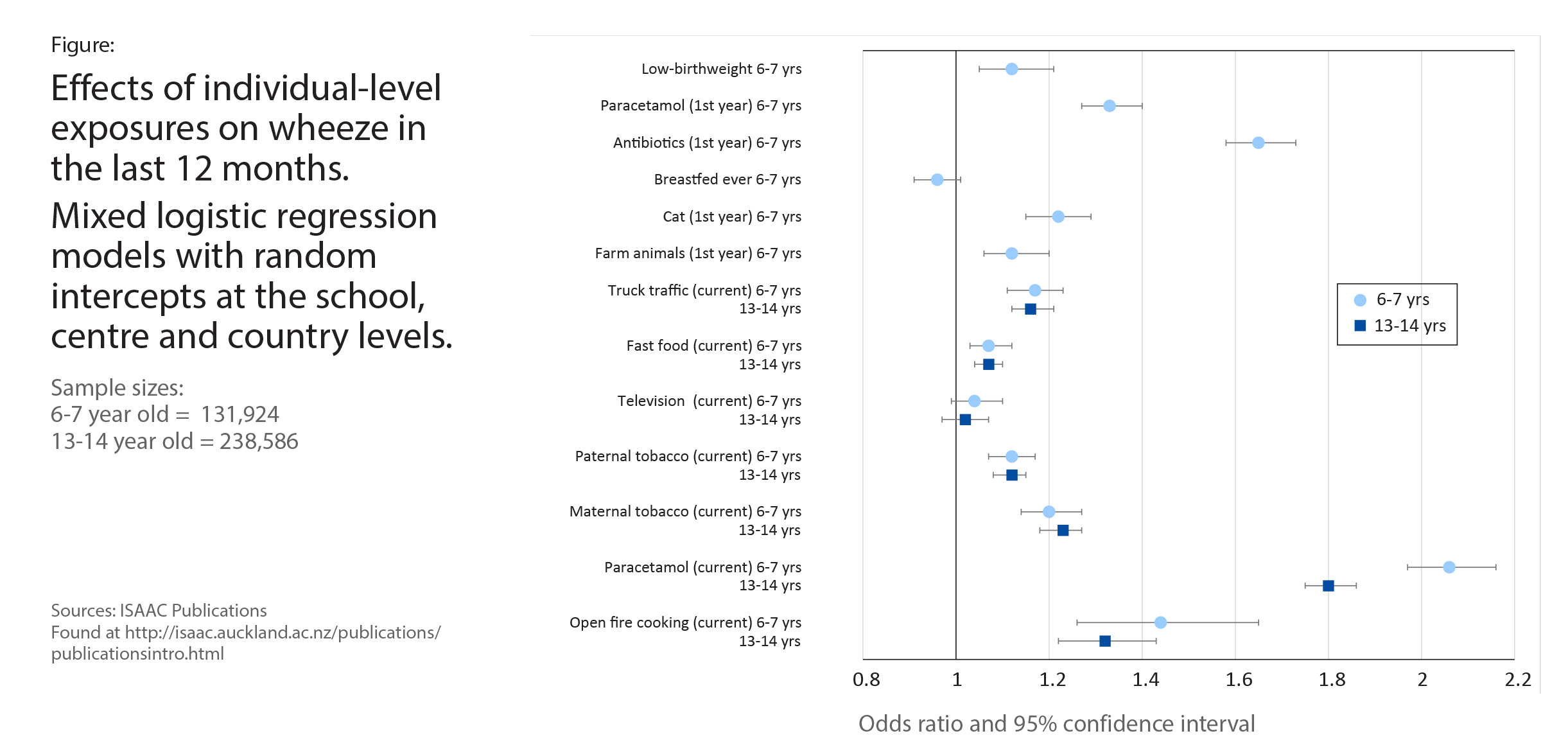

Recent analyses of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Phase Three looked at multiple individual level risk factors for asthma symptoms (Figure) and compared them to risk factors at the sampled school level. The reason to look at schoollevel effects is that an individual may change their behaviour if they (or their children) develop asthma, and this may bias the results of individual-level analyses, known as reverse causation. However, such a behaviour change would have only a small effect at the school-level. The strongest individual-level associations for asthma symptoms in 6-7 year olds were current paracetamol use, early life antibiotic use and open fire cooking, with consistent results at schoollevel. For 13-14 year olds, the strongest individuallevel associations were with current paracetamol use, open fire cooking and maternal tobacco use, again with consistent results at school-level. These consistencies provide evidence against reverse causation, thus strengthening the evidence for a causal relationship between these risk factors and asthma.

Conclusion

Environmental factors are much more likely than genetic factors to have caused the large increase in the numbers of people in the world with asthma, but we still do not know all the factors and how they interact with each other and with genes. Some of these factors may not act in the same way in HICs and LMICs.

Next: Cost-effectiveness of Asthma Management using Inhaled Corticosteroids >